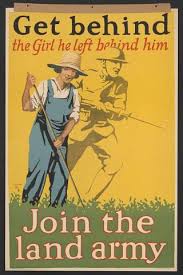

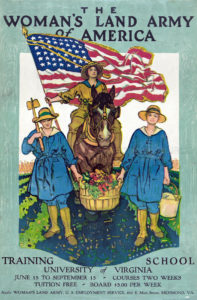

Between 1917 and 1919 roughly 20,000 women served in the Women’s Land Army of America. Known as “Farmerettes,” these mostly young ladies came from all backgrounds and regions of the United States. They helped keep food on the tables of everyday Americans throughout the Great War. 1

A Bit of Background…

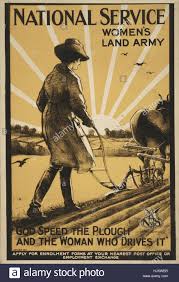

It’s 1915, and, imagine, if you will, a chilly July afternoon in London, where throngs of women are marching, demanding “their right to serve” their country during the war. 2

Although Emmeline Pankhurst, the famous suffragette leader, is at the head of the crowds, the event was put together by the British Government. David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, organized this rally because he knew that Britain was going to need help on the home front during this “War to End All Wars.” 3

An ocean away, the United States was not completely isolated from the growing storm in Europe. By 1916, America was sending food to France. And, many citizens foresaw the rising conflict overseas, and anticipated that the United States would become involved. The National Security League was one of the organizations that arose before our entry into World War 1 and was focused on defending America.

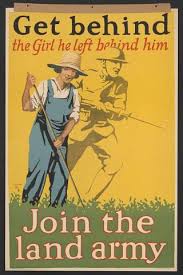

Miss Grace Parker, who had joined America’s National Security League, went to England to visit with members of the Women’s Land Army of Great Britain, which, ultimately became a model for America’s Women’s Land Army of the United States. 4

Upon her return, she addressed the Congress of Constructive Patriotism, an event that was held in New York in January 25-27,1917. 5

Her speech, entitled,“Woman Power of the Nation,” was lauded by the more 3000 businesspeople, Senators, Governors, Mayors, Generals and others who attended the Congress, inspiring them onto action. One of the outcomes of this event was the formation of The National League for Women’s Service, a group designed to galvanize this “Woman Power.” 6

Their mission was:

“To coordinate and standardize the work of women of America along lines of constructive patriotism; to develop the resources, to promote the efficiency of women in meeting their every-day responsibility to home, to state, to nation and to humanity; to provide organized, trained groups in every community prepared to cooperate with the Red Cross and other agencies in dealing with any calamity-fire, flood, famine, economic disorder, etc., and in time of war, to supplement the work of the Red Cross, the Army and Navy, and to deal with the questions of “Woman’s Work and Woman’s Welfare.” 7

Their organization’s slogan was “for God, for Country, for Home.”8

On January 31, 1917 the German Government announced that, on February 1, 1917, it would no longer restrict their submarines from firing on any ship (merchant ships from neutral countries, passenger ships, etc.) that sailed in the war zone around Britain, France and in the Mediterranean Sea. On February 3, the United States broke diplomatic relations with Germany. True to their promise, the high command gave orders for the submarines to attack, and before April 6, 1917, they had sunk 9 American ships, and caused the U.S. to lose another due explosion by underwater mines. 9

All this began less than two weeks after Grace Parker addressed the Congress of Constructive Patriotism about harnessing the “Woman Power of the Nation.”

The sinking of the ships was the final straw. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress requesting a declaration of War on Germany. The motion was passed

by the Senate on April 4, 1917 and by the House on April 6, 1917.

The United States officially entered World War 1 with its’ Declaration of War on April 6, 1917. 10

The newly formed National League for Women’s Service marshaled forces and got busy. Working in conjunction with the Red Cross, they developed

“…thirteen national divisions, as follows: Social and Welfare, Home Economics, Agricultural, Industrial, Medical and Nursing, Motor Driving, General Service, Health, Civics, Signalling, Map-reading, Wireless and Telegraphy, and Camping. Definite work under these thirteen national divisions … developed through state and local organizations, the working unit being a detachment of not less than ten nor over thirty under the direction of a detachment commander.”11

So, it began, that American women began to take up the work of their men who were off at war, performing the duties of: dockworkers, bricklayers, coalminers, munitions workers, nurses, teachers, wireless operators, ambulance drivers, drivers, railroad conductors, farmerettes and other jobs as needed.

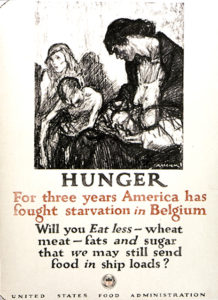

Food production had become a critical issue. In late February, 1917, Bread Riots broke out in New York, Philadelphia and Chicago. Shortages developed because the United States had been sending food to France since 1916. Subsequently, prices on staples had risen astronomically making it difficult for people to buy the basics. Agricultural support was deemed a priority at all levels of government. 12

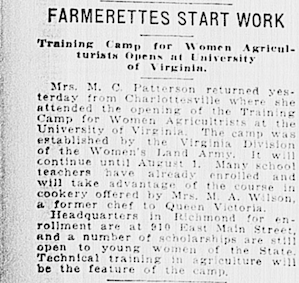

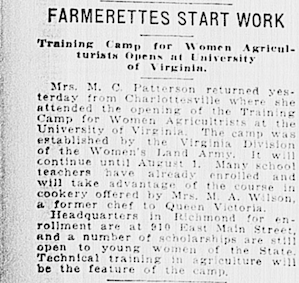

Enter the Women’s Land Army of America (WLA). “Farmerettes,” as they became known, hailed from all over the United States, came from all walks of life and many, many of them had no experience with farming. But, they were anxious to “Do Their Bit,” and enthusiastic about their mission. Although the members of the WLA were of all ages, many were young and excited about the adventures that awaited them as they took their turn at farm life. Many were students who attended institutions such as Barnard College, Bryn Mawr, Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, Goucher, Vassar, Mount Holyoke and others throughout the United States. The Northeast, Midwest, West and some Southern states embraced the WLAA. Camps where the women were housed and received much-needed training, included New York, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Michigan, New Mexico, New Hampshire, New Jersey,Virginia, Illinois, Alabama, Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina and California. 13

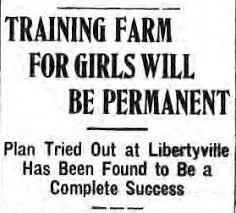

They found out that farming was a tough business. Graduation from the Libertyville farm in Illinois was thusly described in a Chicago Tribune article:

“There was no organdy and lace, no pink ribbons and rosebuds about the graduation dresses of the girl farmers who met in the leafy grove on the farm of the Woman’s Land Army yesterday. The graduates wore overalls instead, garments which had obviously seen hard service. A bright kerchief worn about the neck or the head, a feather placed Indian fashion in the hair–these were the only signs of ‘dressing up.’ They realized they were there as pioneers in a new work for women.” 14

Armed with knowledge and training, they were ready with rakes, hoes, trowels and shovels, in hand. The only problem was that the farmers didn’t necessarily trust them. Despite the great need for food production, in many cases it took enormous amounts of persuasion on the part of the WLA Camp Directors, local media, local politicians and business leaders to convince farmers to hire this new and very dedicated work force. 15

In an address in September 17, 1918 at the Illinois Training Farm for Land Army Women, Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden, explained to farmers:

“My old friend, the Conservative Farmer: I know that many of you think that these girls will not do on the farm. I welcome these young women into our ranks…These young women who shall help us to raise the food to feed their brothers on the battle front… And by helping us to raise the food we need, will become comrades of these heroic boys in the trenches of battle fronts of Europe.

“I hope that this movement begun here in a simple, modest but very effective manner, may communicate itself to other portions of this State and other States so that if need be we will match the irresistible army of our heroic men on the battlefront with an equally strong and equally patriotic army of women in the field and in the dairies of our land.” 16

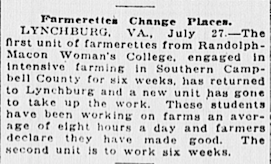

At Randolph-Macon Woman’s College (RMWC), in Lynchburg, Virginia, Dr. Meta Glass, a young Professor of Latin, directed the school’s group of Farmerettes. Dr. Glass, herself, an alumna of RMWC, took her charges to farms around the Virginia Piedmont where they could work the land and help with harvests. 17

Likewise, Farmerettes brought in crops of peaches, apples, potatoes, tobacco, beans, corn and every fruit and vegetable conceivable. They plowed, raked, hoed, dug, built fences and coops, herded cattle, sheep and goats. They milked cows, tended pigs and chickens — in short, they did every sort of farm work available.

But, what did the ladies think? Here are some of descriptions:

Here are some thoughts from Helen Kennedy Stevens, a senior at Barnard College, who served at the Bedford Camp,

“…apple picking in an old orchard, where we had to use forty-foot ladders. Coming down a forty-foot ladder with a full basket of apples is a circus stunt, I can tell you. Then there was cutting and loading corn for the silo, and potato digging was also a husky harvesting job. The corn cutting was picturesque, but the corn rash we got was not. Preparation for a day in corn was chiefly putting old stockings on our arms.” 18

Letter from a farmerette in a Staten Island, N.Y Land Army unit, 1918:

This isn’t like any other camp for man, woman, or child. It is at times the jolliest,

but always the most strenuous, ever. Rise 5:30; tumble downstairs in the dark for a hose pipe shower; overalls on. breakfast with a cafeteria rush; bed-making; grab a lunch; jump into the Ford with ten to twenty others whom a natty little chaufferette delivers at several farms within a radius of six miles by 7:30; hoe, weed, plant or gather and carry bushels of luscious tomatoes, until the noon whistle blows; lunch under the trees with perhaps a few minutes nap in the long grass; then farm work with the farmer till the long Ford comes with our driver in Fifth Avenue togs to take us home again. Can you beat it, the Woman’s Land Army Plattsburg Camp?

At home there is a rush for the porcelain tubs and hot baths, a rush for the laundry tubs to put underclothes and overalls to soak. Dinner at 6, dishes washed, lunches for the next day packed, and assignments made of next day’s work. A spin down to the beach for a salt-water swim, a coolish ride home with the girls hanging on anywhere the Ford offers a foothold and singing lustily. 19

Or

Memoir of Margurite Wilkinson: My Experince as a Farmerette

Chop,chop,chop went our hoes. Down the long field in the hot sun we trudged slowly, hilling up those sprawling plants. Sally could very nearly do two rows while I was doing one, but she cheered me along kindly and tactfully, telling me that I was doing very well indeed for a new girl and that it would be a lot easier when I had grown accustomed to it. Bertha did not work much faster than I, but she was steadier and did not have to stop for breath so often.

Chop,chop,chop. Birds were singing in the trees that bordered the field, Bumble bees buzzed along on their way to neighboring patches of wild flowers. But after a while I was only conscious of the fact that my back, my right wrist, and my left elbow ached like mad.

We went to the house for a pail of water. We took long draughts of it, left the pail under a big tree to keep cool and went back to work. We were painfully conscious of profuse perspiration. They have another word for perspiration on the farms which is more vulgar, vigorous and appropriate. Big drops of moisture were running down our foreheads into our eyes, down our necks into our clothing, down our legs into our mute, protective boots. But for the rest of the morning we kept an honest pace, stopping occasionally for a drink when our progress down the rows took us near the big tree and the tin pail. And at last came noon and the chance to rest.”

In those hours of the afternoon the heat was at its worst. The air seemed to be vivid with it and quivered about our faces. We felt it rising from the soil against the stiff, leather soles of our boots. We were aching, and dripping wet. Little shivers ran up and down our spines occasionally. But we did not stop. We just thought of the boys in the trenches who have much more to bear. Sometimes we spoke of them.

“You see, it is a course in many things besides agriculture, and the camp is a democracy, and cosmopolitan at that. Across the furrows at her weeding, a little Russian tells of her recent voyage to America. Further in among the celery beds a French girl and an Irish girl exchange consolation for the lover and the husband who recently started ‘over there’. College girls, important in their senior years, and women weary of degrees and world travel, wisdom or teaching, come here and take the kink out of tired nerves by straining their flabby muscles a bit. There are violinists in the camp, and singers, too, that the world will yet hear from. ..The war is not talked about thought it lies deep in the hearts of the sweethearts and sisters who are trying to do their bit to increase the country’s food supply.” 20

From the Spring of 1917 through the Fall of 1919, these women saved the day by raising crops in America. These crops fed the U.S. and contributed heavily to foodstuffs for Europe. They certainly “did their bit” and did it very well! We would have been hard-pressed to feed ourselves without them. As the “Great War” ended and the men came home, the WLA gradually packed up its’ shovels and rakes and turned the soil for a last time. The WLA was absorbed into the Department of Labor, but, for all intents and purposes it ceased to exist. 21 It was, however, revived during World War II, but that is another story for another day.

Elaine Weiss, Smithsonian.com, “Before Rosie the Riveter, Farmerettes Went to Work,” May 28, 2009

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 3

Ibid, pp. 4

Ibid, pp. 17

Ida Clyde Clarke. American Women and the World War. Chapter XIV. http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/Clarke/Clarke14.htm

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

9.Rodney Carlisle, “The Attacks on U. S. Shipping that Precipitated American Entry into World War I”

10.First World War.com Primary Documents -…Declaration of War with Germany, 2 April, 1917 m/source/usawardeclaration.htm

11. Ida Clyde Clarke. American Women and the World War. Chapter XIV. http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/Clarke/Clarke14.htm

12.World War I — United States Food Administration U.S. Food Administration http://histclo.com/essay/war/ww1/cou/us/food/w1cus-usfa.html

Wikipedia, Woman’s Land Army of America, World War I,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman%27s_Land_Army_of_America

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 159

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 160 – 161

17. Richmond Times-Dispatch,1918 June 2

Randolph-Macon

[Special to The Times-Dispatch.]

Lynchburg, VA., June 1. ( https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/)

18. Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 83

FARMERETTES – Looking for Mabel Normand. www.freewebs.com

Ibid

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 269

Between 1917 and 1919 roughly 20,000 women served in the Women’s Land Army of America. Known as “Farmerettes,” these mostly young ladies came from all backgrounds and regions of the United States. They helped keep food on the tables of everyday Americans throughout the Great War. 1

A Bit of Background…

It’s 1915, and, imagine, if you will, a chilly July afternoon in London, where throngs of women are marching, demanding “their right to serve” their country during the war. 2

Although Emmeline Pankhurst, the famous suffragette leader, is at the head of the crowds, the event was put together by the British Government. David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, organized this rally because he knew that Britain was going to need help on the home front during this “War to End All Wars.” 3

An ocean away, the United States was not completely isolated from the growing storm in Europe. By 1916, America was sending food to France. And, many citizens foresaw the rising conflict overseas, and anticipated that the United States would become involved. The National Security League was one of the organizations that arose before our entry into World War 1 and was focused on defending America.

Miss Grace Parker, who had joined America’s National Security League, went to England to visit with members of the Women’s Land Army of Great Britain, which, ultimately became a model for America’s Women’s Land Army of the United States. 4

Upon her return, she addressed the Congress of Constructive Patriotism, an event that was held in New York in January 25-27,1917. 5

Her speech, entitled,“Woman Power of the Nation,” was lauded by the more 3000 businesspeople, Senators, Governors, Mayors, Generals and others who attended the Congress, inspiring them onto action. One of the outcomes of this event was the formation of The National League for Women’s Service, a group designed to galvanize this “Woman Power.” 6

Their mission was:

“To coordinate and standardize the work of women of America along lines of constructive patriotism; to develop the resources, to promote the efficiency of women in meeting their every-day responsibility to home, to state, to nation and to humanity; to provide organized, trained groups in every community prepared to cooperate with the Red Cross and other agencies in dealing with any calamity-fire, flood, famine, economic disorder, etc., and in time of war, to supplement the work of the Red Cross, the Army and Navy, and to deal with the questions of “Woman’s Work and Woman’s Welfare.” 7

Their organization’s slogan was “for God, for Country, for Home.”8

On January 31, 1917 the German Government announced that, on February 1, 1917, it would no longer restrict their submarines from firing on any ship (merchant ships from neutral countries, passenger ships, etc.) that sailed in the war zone around Britain, France and in the Mediterranean Sea. On February 3, the United States broke diplomatic relations with Germany. True to their promise, the high command gave orders for the submarines to attack, and before April 6, 1917, they had sunk 9 American ships, and caused the U.S. to lose another due explosion by underwater mines. 9

All this began less than two weeks after Grace Parker addressed the Congress of Constructive Patriotism about harnessing the “Woman Power of the Nation.”

The sinking of the ships was the final straw. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress requesting a declaration of War on Germany. The motion was passed

by the Senate on April 4, 1917 and by the House on April 6, 1917.

The United States officially entered World War 1 with its’ Declaration of War on April 6, 1917. 10

The newly formed National League for Women’s Service marshaled forces and got busy. Working in conjunction with the Red Cross, they developed

“…thirteen national divisions, as follows: Social and Welfare, Home Economics, Agricultural, Industrial, Medical and Nursing, Motor Driving, General Service, Health, Civics, Signalling, Map-reading, Wireless and Telegraphy, and Camping. Definite work under these thirteen national divisions … developed through state and local organizations, the working unit being a detachment of not less than ten nor over thirty under the direction of a detachment commander.”11

So, it began, that American women began to take up the work of their men who were off at war, performing the duties of: dockworkers, bricklayers, coalminers, munitions workers, nurses, teachers, wireless operators, ambulance drivers, drivers, railroad conductors, farmerettes and other jobs as needed.

Food production had become a critical issue. In late February, 1917, Bread Riots broke out in New York, Philadelphia and Chicago. Shortages developed because the United States had been sending food to France since 1916. Subsequently, prices on staples had risen astronomically making it difficult for people to buy the basics. Agricultural support was deemed a priority at all levels of government. 12

Enter the Women’s Land Army of America (WLA). “Farmerettes,” as they became known, hailed from all over the United States, came from all walks of life and many, many of them had no experience with farming. But, they were anxious to “Do Their Bit,” and enthusiastic about their mission. Although the members of the WLA were of all ages, many were young and excited about the adventures that awaited them as they took their turn at farm life. Many were students who attended institutions such as Barnard College, Bryn Mawr, Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, Goucher, Vassar, Mount Holyoke and others throughout the United States. The Northeast, Midwest, West and some Southern states embraced the WLAA. Camps where the women were housed and received much-needed training, included New York, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Michigan, New Mexico, New Hampshire, New Jersey,Virginia, Illinois, Alabama, Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina and California. 13

They found out that farming was a tough business. Graduation from the Libertyville farm in Illinois was thusly described in a Chicago Tribune article:

“There was no organdy and lace, no pink ribbons and rosebuds about the graduation dresses of the girl farmers who met in the leafy grove on the farm of the Woman’s Land Army yesterday. The graduates wore overalls instead, garments which had obviously seen hard service. A bright kerchief worn about the neck or the head, a feather placed Indian fashion in the hair–these were the only signs of ‘dressing up.’ They realized they were there as pioneers in a new work for women.” 14

Armed with knowledge and training, they were ready with rakes, hoes, trowels and shovels, in hand. The only problem was that the farmers didn’t necessarily trust them. Despite the great need for food production, in many cases it took enormous amounts of persuasion on the part of the WLA Camp Directors, local media, local politicians and business leaders to convince farmers to hire this new and very dedicated work force. 15

In an address in September 17, 1918 at the Illinois Training Farm for Land Army Women, Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden, explained to farmers:

“My old friend, the Conservative Farmer: I know that many of you think that these girls will not do on the farm. I welcome these young women into our ranks…These young women who shall help us to raise the food to feed their brothers on the battle front… And by helping us to raise the food we need, will become comrades of these heroic boys in the trenches of battle fronts of Europe.

“I hope that this movement begun here in a simple, modest but very effective manner, may communicate itself to other portions of this State and other States so that if need be we will match the irresistible army of our heroic men on the battlefront with an equally strong and equally patriotic army of women in the field and in the dairies of our land.” 16

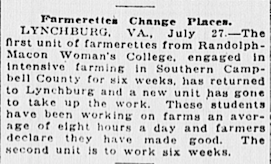

At Randolph-Macon Woman’s College (RMWC), in Lynchburg, Virginia, Dr. Meta Glass, a young Professor of Latin, directed the school’s group of Farmerettes. Dr. Glass, herself, an alumna of RMWC, took her charges to farms around the Virginia Piedmont where they could work the land and help with harvests. 17

Likewise, Farmerettes brought in crops of peaches, apples, potatoes, tobacco, beans, corn and every fruit and vegetable conceivable. They plowed, raked, hoed, dug, built fences and coops, herded cattle, sheep and goats. They milked cows, tended pigs and chickens — in short, they did every sort of farm work available.

But, what did the ladies think? Here are some of descriptions:

Here are some thoughts from Helen Kennedy Stevens, a senior at Barnard College, who served at the Bedford Camp,

“…apple picking in an old orchard, where we had to use forty-foot ladders. Coming down a forty-foot ladder with a full basket of apples is a circus stunt, I can tell you. Then there was cutting and loading corn for the silo, and potato digging was also a husky harvesting job. The corn cutting was picturesque, but the corn rash we got was not. Preparation for a day in corn was chiefly putting old stockings on our arms.” 18

Letter from a farmerette in a Staten Island, N.Y Land Army unit, 1918:

This isn’t like any other camp for man, woman, or child. It is at times the jolliest,

but always the most strenuous, ever. Rise 5:30; tumble downstairs in the dark for a hose pipe shower; overalls on. breakfast with a cafeteria rush; bed-making; grab a lunch; jump into the Ford with ten to twenty others whom a natty little chaufferette delivers at several farms within a radius of six miles by 7:30; hoe, weed, plant or gather and carry bushels of luscious tomatoes, until the noon whistle blows; lunch under the trees with perhaps a few minutes nap in the long grass; then farm work with the farmer till the long Ford comes with our driver in Fifth Avenue togs to take us home again. Can you beat it, the Woman’s Land Army Plattsburg Camp?

At home there is a rush for the porcelain tubs and hot baths, a rush for the laundry tubs to put underclothes and overalls to soak. Dinner at 6, dishes washed, lunches for the next day packed, and assignments made of next day’s work. A spin down to the beach for a salt-water swim, a coolish ride home with the girls hanging on anywhere the Ford offers a foothold and singing lustily. 19

Or

Memoir of Margurite Wilkinson: My Experince as a Farmerette

Chop,chop,chop went our hoes. Down the long field in the hot sun we trudged slowly, hilling up those sprawling plants. Sally could very nearly do two rows while I was doing one, but she cheered me along kindly and tactfully, telling me that I was doing very well indeed for a new girl and that it would be a lot easier when I had grown accustomed to it. Bertha did not work much faster than I, but she was steadier and did not have to stop for breath so often.

Chop,chop,chop. Birds were singing in the trees that bordered the field, Bumble bees buzzed along on their way to neighboring patches of wild flowers. But after a while I was only conscious of the fact that my back, my right wrist, and my left elbow ached like mad.

We went to the house for a pail of water. We took long draughts of it, left the pail under a big tree to keep cool and went back to work. We were painfully conscious of profuse perspiration. They have another word for perspiration on the farms which is more vulgar, vigorous and appropriate. Big drops of moisture were running down our foreheads into our eyes, down our necks into our clothing, down our legs into our mute, protective boots. But for the rest of the morning we kept an honest pace, stopping occasionally for a drink when our progress down the rows took us near the big tree and the tin pail. And at last came noon and the chance to rest.”

In those hours of the afternoon the heat was at its worst. The air seemed to be vivid with it and quivered about our faces. We felt it rising from the soil against the stiff, leather soles of our boots. We were aching, and dripping wet. Little shivers ran up and down our spines occasionally. But we did not stop. We just thought of the boys in the trenches who have much more to bear. Sometimes we spoke of them.

“You see, it is a course in many things besides agriculture, and the camp is a democracy, and cosmopolitan at that. Across the furrows at her weeding, a little Russian tells of her recent voyage to America. Further in among the celery beds a French girl and an Irish girl exchange consolation for the lover and the husband who recently started ‘over there’. College girls, important in their senior years, and women weary of degrees and world travel, wisdom or teaching, come here and take the kink out of tired nerves by straining their flabby muscles a bit. There are violinists in the camp, and singers, too, that the world will yet hear from. ..The war is not talked about thought it lies deep in the hearts of the sweethearts and sisters who are trying to do their bit to increase the country’s food supply.” 20

From the Spring of 1917 through the Fall of 1919, these women saved the day by raising crops in America. These crops fed the U.S. and contributed heavily to foodstuffs for Europe. They certainly “did their bit” and did it very well! We would have been hard-pressed to feed ourselves without them. As the “Great War” ended and the men came home, the WLA gradually packed up its’ shovels and rakes and turned the soil for a last time. The WLA was absorbed into the Department of Labor, but, for all intents and purposes it ceased to exist. 21 It was, however, revived during World War II, but that is another story for another day.

Elaine Weiss, Smithsonian.com, “Before Rosie the Riveter, Farmerettes Went to Work,” May 28, 2009

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 3

Ibid, pp. 4

Ibid, pp. 17

Ida Clyde Clarke. American Women and the World War. Chapter XIV. http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/Clarke/Clarke14.htm

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

9.Rodney Carlisle, “The Attacks on U. S. Shipping that Precipitated American Entry into World War I”

10.First World War.com Primary Documents -…Declaration of War with Germany, 2 April, 1917 m/source/usawardeclaration.htm

11. Ida Clyde Clarke. American Women and the World War. Chapter XIV. http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/Clarke/Clarke14.htm

12.World War I — United States Food Administration U.S. Food Administration http://histclo.com/essay/war/ww1/cou/us/food/w1cus-usfa.html

Wikipedia, Woman’s Land Army of America, World War I,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman%27s_Land_Army_of_America

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 159

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 160 – 161

17. Richmond Times-Dispatch,1918 June 2

Randolph-Macon

[Special to The Times-Dispatch.]

Lynchburg, VA., June 1. ( https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/)

18. Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 83

FARMERETTES – Looking for Mabel Normand. www.freewebs.com

Ibid

Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 269

Between 1917 and 1919 roughly 20,000 women served in the Woman’s Land Army of America (WLA). Known as “Farmerettes,” these mostly young ladies came from all backgrounds and regions of the United States. They helped keep food on the tables of everyday Americans throughout the Great War. 1

A Bit of Background…

It’s 1915, and, imagine, if you will, a chilly July afternoon in London, where throngs of women are marching, demanding “their right to serve” their country during the war. 2

Although Emmeline Pankhurst, the famous suffragette leader, is at the head of the crowds, the event was put together by the British Government. David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, organized this rally because he knew that Britain was going to need help on the home front during this “War to End All Wars.” 3

An ocean away, the United States was not completely isolated from the growing storm in Europe. By 1916, America was sending food to France. And, many citizens foresaw the rising conflict overseas, and anticipated that the United States would become involved. The National Security League was one of the organizations that arose before our entry into World War 1 and was focused on defending America.

Miss Grace Parker, who had joined America’s National Security League, went to England to visit with members of the Women’s Land Army of Great Britain, which, ultimately became a model for America’s Women’s Land Army of the United States. 4

Upon her return, she addressed the Congress of Constructive Patriotism, an event that was held in New York in January 25-27,1917. 5

Her speech, entitled,“Woman Power of the Nation,” was lauded by the more 3000 businesspeople, Senators, Governors, Mayors, Generals and others who attended the Congress, inspiring them onto action. One of the outcomes of this event was the formation of The National League for Women’s Service, a group designed to galvanize this “Woman Power.” 6

Their mission was:

“To coordinate and standardize the work of women of America along lines of constructive patriotism; to develop the resources, to promote the efficiency of women in meeting their every-day responsibility to home, to state, to nation and to humanity; to provide organized, trained groups in every community prepared to cooperate with the Red Cross and other agencies in dealing with any calamity-fire, flood, famine, economic disorder, etc., and in time of war, to supplement the work of the Red Cross, the Army and Navy, and to deal with the questions of “Woman’s Work and Woman’s Welfare.” 7

Their organization’s slogan was “for God, for Country, for Home.”8

On January 31, 1917 the German Government announced that, on February 1, 1917, it would no longer restrict their submarines from firing on any ship (merchant ships from neutral countries, passenger ships, etc.) that sailed in the war zone around Britain, France and in the Mediterranean Sea. On February 3, the United States broke diplomatic relations with Germany. True to their promise, the high command gave orders for the submarines to attack, and before April 6, 1917, they had sunk 9 American ships, and caused the U.S. to lose another due explosion by underwater mines. 9

All this began less than two weeks after Grace Parker addressed the Congress of Constructive Patriotism about harnessing the “Woman Power of the Nation.”

The sinking of the ships was the final straw. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress requesting a declaration of War on Germany. The motion was passed by the Senate on April 4, 1917 and by the House on April 6, 1917.

The United States officially entered World War 1 with its’ Declaration of War on April 6, 1917. 10

The newly formed National League for Women’s Service marshaled forces and got busy. Working in conjunction with the Red Cross, they developed

“…thirteen national divisions, as follows: Social and Welfare, Home Economics, Agricultural, Industrial, Medical and Nursing, Motor Driving, General Service, Health, Civics, Signalling, Map-reading, Wireless and Telegraphy, and Camping. Definite work under these thirteen national divisions … developed through state and local organizations, the working unit being a detachment of not less than ten nor over thirty under the direction of a detachment commander.”11

So, it began, that American women began to take up the work of their men who were off at war, performing the duties of: dockworkers, bricklayers, coalminers, munitions workers, nurses, teachers, wireless operators, ambulance drivers, drivers, railroad conductors, farmerettes and other jobs as needed.

Food production had become a critical issue. In late February, 1917, Bread Riots broke out in New York, Philadelphia and Chicago. Shortages developed because the United States had been sending food to France since 1916. Subsequently, prices on staples had risen astronomically making it difficult for people to buy the basics. Agricultural support was deemed a priority at all levels of government. 12

Enter the Women’s Land Army of America (WLA). “Farmerettes,” as they became known, hailed from all over the United States, came from all walks of life and many, many of them had no experience with farming. But, they were anxious to “Do Their Bit,” and enthusiastic about their mission. Although the members of the WLA were of all ages, many were young and excited about the adventures that awaited them as they took their turn at farm life. Many were students who attended institutions such as Barnard College, Bryn Mawr, Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, Goucher, Vassar, Mount Holyoke and others throughout the United States. The Northeast, Midwest, West and some Southern states embraced the WLAA. Camps where the women were housed and received much-needed training, included New York, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Michigan, New Mexico, New Hampshire, New Jersey,Virginia, Illinois, Alabama, Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina and California. 13

They found out that farming was a tough business. Graduation from the Libertyville farm in Illinois was thusly described in a Chicago Tribune article:

“There was no organdy and lace, no pink ribbons and rosebuds about the graduation dresses of the girl farmers who met in the leafy grove on the farm of the Woman’s Land Army yesterday. The graduates wore overalls instead, garments which had obviously seen hard service. A bright kerchief worn about the neck or the head, a feather placed Indian fashion in the hair–these were the only signs of ‘dressing up.’ They realized they were there as pioneers in a new work for women.” 14

Armed with knowledge and training, they were ready with rakes, hoes, trowels and shovels, in hand. The only problem was that the farmers didn’t necessarily trust them. Despite the great need for food production, in many cases it took enormous amounts of persuasion on the part of the WLA Camp Directors, local media, local politicians and business leaders to convince farmers to hire this new and very dedicated work force. 15

In an address in September 17, 1918 at the Illinois Training Farm for Land Army Women, Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden, explained to farmers:

“My old friend, the Conservative Farmer: I know that many of you think that these girls will not do on the farm. I welcome these young women into our ranks…These young women who shall help us to raise the food to feed their brothers on the battle front… And by helping us to raise the food we need, will become comrades of these heroic boys in the trenches of battle fronts of Europe.

“I hope that this movement begun here in a simple, modest but very effective manner, may communicate itself to other portions of this State and other States so that if need be we will match the irresistible army of our heroic men on the battlefront with an equally strong and equally patriotic army of women in the field and in the dairies of our land.” 16

At Randolph-Macon Woman’s College (RMWC), in Lynchburg, Virginia, Dr. Meta Glass, a young Professor of Latin, directed the school’s group of Farmerettes. Dr. Glass, herself, an alumna of RMWC, took her charges to farms around the Virginia Piedmont where they could work the land and help with harvests. 17

Likewise, Farmerettes brought in crops of peaches, apples, potatoes, tobacco, beans, corn and every fruit and vegetable conceivable. They plowed, raked, hoed, dug, built fences and coops, herded cattle, sheep and goats. They milked cows, tended pigs and chickens — in short, they did every sort of farm work available.

But, what did the ladies think? Here are some of descriptions:

Here are some thoughts from Helen Kennedy Stevens, a senior at Barnard College, who served at the Bedford Camp,

“…apple picking in an old orchard, where we had to use forty-foot ladders. Coming down a forty-foot ladder with a full basket of apples is a circus stunt, I can tell you. Then there was cutting and loading corn for the silo, and potato digging was also a husky harvesting job. The corn cutting was picturesque, but the corn rash we got was not. Preparation for a day in corn was chiefly putting old stockings on our arms.” 18

Letter from a farmerette in a Staten Island, N.Y Land Army unit, 1918:

This isn’t like any other camp for man, woman, or child. It is at times the jolliest,

but always the most strenuous, ever. Rise 5:30; tumble downstairs in the dark for a hose pipe shower; overalls on. breakfast with a cafeteria rush; bed-making; grab a lunch; jump into the Ford with ten to twenty others whom a natty little chaufferette delivers at several farms within a radius of six miles by 7:30; hoe, weed, plant or gather and carry bushels of luscious tomatoes, until the noon whistle blows; lunch under the trees with perhaps a few minutes nap in the long grass; then farm work with the farmer till the long Ford comes with our driver in Fifth Avenue togs to take us home again. Can you beat it, the Woman’s Land Army Plattsburg Camp?

At home there is a rush for the porcelain tubs and hot baths, a rush for the laundry tubs to put underclothes and overalls to soak. Dinner at 6, dishes washed, lunches for the next day packed, and assignments made of next day’s work. A spin down to the beach for a salt-water swim, a coolish ride home with the girls hanging on anywhere the Ford offers a foothold and singing lustily. 19

Or

Memoir of Margurite Wilkinson: My Experince as a Farmerette

Chop,chop,chop went our hoes. Down the long field in the hot sun we trudged slowly, hilling up those sprawling plants. Sally could very nearly do two rows while I was doing one, but she cheered me along kindly and tactfully, telling me that I was doing very well indeed for a new girl and that it would be a lot easier when I had grown accustomed to it. Bertha did not work much faster than I, but she was steadier and did not have to stop for breath so often.

Chop,chop,chop. Birds were singing in the trees that bordered the field, Bumble bees buzzed along on their way to neighboring patches of wild flowers. But after a while I was only conscious of the fact that my back, my right wrist, and my left elbow ached like mad.

We went to the house for a pail of water. We took long draughts of it, left the pail under a big tree to keep cool and went back to work. We were painfully conscious of profuse perspiration. They have another word for perspiration on the farms which is more vulgar, vigorous and appropriate. Big drops of moisture were running down our foreheads into our eyes, down our necks into our clothing, down our legs into our mute, protective boots. But for the rest of the morning we kept an honest pace, stopping occasionally for a drink when our progress down the rows took us near the big tree and the tin pail. And at last came noon and the chance to rest.”

In those hours of the afternoon the heat was at its worst. The air seemed to be vivid with it and quivered about our faces. We felt it rising from the soil against the stiff, leather soles of our boots. We were aching, and dripping wet. Little shivers ran up and down our spines occasionally. But we did not stop. We just thought of the boys in the trenches who have much more to bear. Sometimes we spoke of them.

“You see, it is a course in many things besides agriculture, and the camp is a democracy, and cosmopolitan at that. Across the furrows at her weeding, a little Russian tells of her recent voyage to America. Further in among the celery beds a French girl and an Irish girl exchange consolation for the lover and the husband who recently started ‘over there’. College girls, important in their senior years, and women weary of degrees and world travel, wisdom or teaching, come here and take the kink out of tired nerves by straining their flabby muscles a bit. There are violinists in the camp, and singers, too, that the world will yet hear from. ..The war is not talked about thought it lies deep in the hearts of the sweethearts and sisters who are trying to do their bit to increase the country’s food supply.” 20

From the Spring of 1917 through the Fall of 1919, these women saved the day by raising crops in America. These crops fed the U.S. and contributed heavily to foodstuffs for Europe. They certainly “did their bit” and did it very well! We would have been hard-pressed to feed ourselves without them. As the “Great War” ended and the men came home, the WLA gradually packed up its’ shovels and rakes and turned the soil for a last time. The WLA was absorbed into the Department of Labor, but, for all intents and purposes it ceased to exist. 21 It was, however, revived during World War II, but that is another story for another day.

1.Elaine Weiss, Smithsonian.com, “Before Rosie the Riveter, Farmerettes Went to Work,” May 28, 2009

2.Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 3

3.Ibid, pp. 4

4.Ibid, pp. 17

5.Ida Clyde Clarke. American Women and the World War. Chapter XIV. http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/Clarke/Clarke14.htm

6.Ibid

7.Ibid

8.Ibid

9.Rodney Carlisle, “The Attacks on U. S. Shipping that Precipitated American Entry into World War I”

10.First World War.com Primary Documents -…Declaration of War with Germany, 2 April, 1917 m/source/usawardeclaration.htm

11. Ida Clyde Clarke. American Women and the World War. Chapter XIV. http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/Clarke/Clarke14.htm

12.World War I — United States Food Administration U.S. Food Administration http://histclo.com/essay/war/ww1/cou/us/food/w1cus-usfa.html

13.Wikipedia, Woman’s Land Army of America, World War I,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman%27s_Land_Army_of_America

14.Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 159

15.Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War

16.Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 160 – 161

17. Richmond Times-Dispatch,1918 June 2,Randolph-Macon[Special to The Times-Dispatch.]Lynchburg, VA., June 1. ( https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/)

18. Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 83

19.FARMERETTES – Looking for Mabel Normand. www.freewebs.com

20.Ibid

21.Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, pp. 269

One reply on “World War One Farmerettes: Working the Land and Feeding the World”

Thanks for sharing such a pleasant thinking,

piece of writing is pleasant, thats why i have read it fully