Feathers, Furs and Lace: The Price of Fashion in 1912

By Dale Paige Talley

I help create costumes and exhibits. We dress characters in period correct attire so they can help people interpret specific historical eras and events. The goal is to make learning fun. Recently I was looking for an idea for a program about Edwardian fashion and thought that since the anniversary of the maiden voyage of RMS (Royal Mail Ship) Titanic is upcoming on April 15, I could use it as a vehicle. Of course the Titanic ended in tragedy and the world still mourns the loss of more than 1500 souls in the icy waters of the Atlantic. But the story of the ill-fated ship lives on in our hearts and minds.

There is so much material about the loss of the ship and the fashions of the era, it is not easy to think of something new to discuss. Sixty seconds on the internet will yield more photographs of dresses, corsets, tea gowns, plumed hats and the always funny hobble skirt than one can digest.

Suddenly, the image of Rose arriving at the dock in one of the early scenes of James Cameron’s 1997 movie Titanic appeared in my consciousness. At first we see only the top of her hat as she extends a gloved hand to be helped out of her limousine. It takes a few seconds before she can raise the brim (it is a big hat,). Finally we see her face looking at the huge ship she is about to board. She has a sophisticated air of “ho-hum” in her gaze. The scene has always reminded me of ugly-duckling turned swan, Charlotte Vale in Irving Rapper’s 1942 film, Now Voyager. In a pivotal scene, Charlotte has been transformed from a dowdy spinster into a model of sleek fashion. She is going on the first real adventure of her life. As she steps aboard a luxury liner, the camera focuses on the top of her wide-brimmed hat. Slowly, she looks up to reveal the new Charlotte eager for the journey to begin. It makes me smile.

In Titanic, the docks are teaming. As Rose’s party emerges from chauffeur-driven limousines, the camera pans over carts piled with steamer trunks, hand baggage and even a safe for precious jewelry, indispensable documents and cash. The irony of the safe is not lost on us. We know what happens.

Today, most of us traveling say from London to New York are minimalists. We don’t want to pay extra baggage fees or wait too long at the baggage claim at the other end. We have elevated taking as little as possible in small suitcases to an art. We fold washable, crush-proof, wrinkle-free, quick-dry garments into small bags that can be dragged on their little wheels behind us through the throngs at international airports. At the boarding gate we line up under covered ramps and quietly move forward to our assigned seats.

First class passengers might have champagne, leather seats and a little more leg room, but all passengers are belted into their seats and hurtled at 35,000 feet above the surface of the earth continent to continent. It takes about eight hours. To pass the time, we thumb through magazines, do crossword puzzles, watch movies, sleep or tell secrets to people we have never met knowing we will never see them again. In the main, the process of travel is something to be endured, not relished. With minor differences, most airlines are the same and there is a quality of cattle car to them all.

But a century ago, during the golden age of travel, the only way to cross the ocean was by steamship, For the glitterati, first class travel was a social event of high style. Historian Andrew Wilson wrote, “Passengers were stratified by class—the third class at the bottom of the ship, the second in the middle, the first at the top—and, for the most part, did not mix with one another. In those massive liners, first, second or third class passengers had completely different experiences.”1

Of course Rose DeWitt Bukater is a fictional character but aboard The White Star Line’s 883 foot Titanic, the real-life first class businessmen, politicians, military brass, sports icons and silent film stars were among those who bought the pricey tickets. Colonel John Jacob Astor embarked with his pregnant wife Madeleine. They were returning from their extended honeymoon in Egypt. Benjamin Guggenheim was traveling with his mistress, French singer Leontine Pauline Aubart. She traveled incognito to avoid scandal. Fashion designer Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon (whose designer label was Lucile) had first class accommodations, as did film actress Dorothy Gibson.

Accustomed to life in the grand hotels of Europe, and luxury liners like The Mauritania and Lusitania, the uber-rich must have been curious to compare the new Titanic, They knew how to entertain themselves and would have ample time to discuss the comparison over Formal dinners signaled by on-deck bugler that could have as many as twelve courses and last four or five hours. The dinners must have been relaxing after a full day of strolling on covered decks, lounging in deck chairs, or having lunch or tea in any of a number of restaurants and cafes. After dinner they could relax a little more. Ladies could retire to the reading room for bridge. For the gentlemen it would be cigars and brandy in the smoking room.

What did they wear for all those dinners, lunches and teas? What did it cost to own the diaphanous gowns that seemed to float in a spangled ether of their own? How expensive were the aigrettes mounted in diamond tiaras, or chinchilla coats and silver fox stoles that kept delicate shoulders warm? What about the intricate lace waists and tea dresses? How much did an extravagantly plumed hat really cost (and why didn’t Rose DeWitt Bukater have any other huge hat)?

The most expensive accommodations on the ship were the two exclusive parlor suites with two bedrooms, bathroom, sitting room and fifty-foot private deck. It is well known that one of the suites had been booked by J. P. Morgan who had to back out just before the ship sailed. A wealthy Philadelphia divorcee, Charlotte Cardeza, purchased the second suite for the equivalent of $62,591 according to Money Magazine’s calculations.2

Mrs. Cardeza famously boarded the ship with three other people and a staggering amount of trunks, suitcases and crates. Who was she and why was she on the Titanic?

Image 1. Charlotte Cardeza circa 1900, Courtesy Thomas Jefferson University Archives

Image 2. Charlotte Cardeza and her son, Thomas aboard their 282 foot steamer-yacht, Eleanor. Courtesy Thomas Jefferson University Archives

Image 3. Charlotte Cardeza game hunting on safari in Africa, 1911. Courtesy Thomas Jefferson University Archives

Charlotte Wardle Drake Martinez-Cardeza was no ordinary traveler. She was also no ordinary woman. Not only was she a member of the Philadelphia elite, she was a fashionista, art buyer, globe-trotting yachtswoman and big-game hunter. She inherited her fortune from her father, a textile manufacturer who invented a method of making denim that was sold to the Union Army during the Civil War.

Though she owned the princely estate known as Montebello in Germantown, Pennsylvania, she spent most of her time aboard her 232-foot steamer-yacht, Eleanor, with its crew of 39. In 1912, her usual entourage included 36 year-old Thomas, his manservant, Gustave J. Lesueur, and her ladies’ maid, Annie Moore Ward. They cruised to the most exotic ports around the world.

In early 1912, mother and son completed an extended trip to Europe and Africa that included a safari. In April, they decided to return home. They elected to book the brand spanking new Titanic. Perhaps because it was her birthday. Charlotte turned 58 the day they boarded Titanic at Cherbourg after a final shopping spree in Paris.

The U. S. National Archives has on file a list of the contents of Mrs. Cardeza’s trunks that were loaded onto the Titanic. The document is fascinating in detail. It is sixteen pages long and single spaced. Many pieces of clothing are detailed by designer, material, color, cost and in many cases where purchased. The document was submitted to the Oceanic Navigation Steamship Company in support of her claim for losses when the Titanic sank. The total value of the clothing in today’s dollars is estimated to be $1,775,000. The jewelry at more than $2,561,000. It could be that the document overvalues her wardrobe, but it is nonetheless a gold mine for fashion historians.

Image 4. Louis Vuitton trunk. Louis Vuitton made history with his sturdy, elegant trunks that were said to be airtight in 1854. Rather than being fined as traditional trunks, his were flat- bottomed and stackable

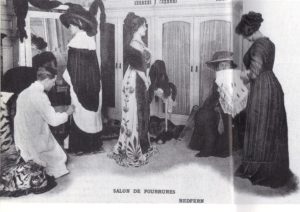

Among the most popular designers of the day were Redfern, Worth, Paquin, Doucet, Callot-Soeurs, and Poiret. Upstart Coco Chanel had not yet hit her stride, though she opened her first salon in 1909. Judging by her inventory, Mrs. Cardeza preferred tradition to cutting edge style. She had several designer garments by Redfern, Worth and Callot-Soeurs. There was a single rose-colored-gown in one of the trunks made by Lucile, but, what would she need to be perfectly decked out amongst the “A” list social crowd for this trip?

A partial summary shows that she needed at least 31 dresses; 39 blouses; 21 nightgowns (all pink, but one); 13 petticoats; 22 Pairs of shoes; 75 pairs of gloves; 12 suits; 11 hats; 58 individual feathers and 45 pairs of stockings. There were ivory combs, false hair, ribbons (one which was described as a ‘hobble’), several pairs of fur-topped slippers and a scarf edged in maribou (stork feathers). She also required an entire trunk full of furs, muffs and stoles.

Image 5. Redfern salon. Established at Cowes in the Isle of Wight in 1855. Redfern became tailor to the Queen of England, Empress of Russia, Princess of Wales and the royal courts of Germany, Portugal, Denmark and Greece, among others.

Image 6. Callot-Soeurs dress 1912

There were unwritten but strict rules about dress for women of the leisure class. A single day could require at least three wardrobe changes. Each transformation had a specific purpose and exacting standards for that purpose. It took five and a half days to make the 2890 mile journey across the Atlantic. First class women never wore the same outfit twice during a crossing. They never dressed in formal attire the first and last evenings. No self-respecting first class lady would think of traveling without a ladies maid to organize, track and layout each wardrobe change with its requisite accessories. Brushing and twisting hair into the appropriate style required assistance. Cleaning, pressing, mending, packing and repacking was not on the agenda for “Madam” who was busy seeing and being seen. Mrs. Cardeza had the efficient Annie Moore Ward traveling with her. It was presumably Ward who prepared the inventory.

During the first quarter of 1912, Vogue magazine revealed the important fashion trends of the season. The byword would be “revival”. Louis XIV touches such as heavy brocade and fine laces would appear on gowns, dresses, jabots, fans, umbrellas, and, well, everything. There would also be a resurrection of columnar Egyptian style dresses in contrasting colors such as green and black. Other important materials in style would be silk chiffon and fine embroidery. Mrs. Cardeza’s inventory showed at least six brocade dresses in her Louis Vuitton, Goyard, Mendel and Innovation trunks. Of course we do not have images of Mrs. Cardeza’s clothing but we can find examples by the well-known couturiers of the time. Of the more than thirty dresses listed, two stand out as being both the most expensive and fashion forward. The first a cream silk chiffon dress designed by Redfern that cost $500.00 (or about $12,300). The second is from Worth that cost $900.00 then or $22,000 today. (As an aside, the dress was not as expensive as the bonbonniere purchased in Paris at the end of her trip for $1,000! It must have been some candy dish.)

Aside from its delicate beauty, lace has had an influence on, history, politics, fashion, culture, and world economies over the millennia. It has always been a status symbol since men (not women) began to wear it centuries ago. Louis XIV strained the French treasury purchasing lace from Italy until he pirated some lace-makers and brought them to France to make a better domestic product. If the inventory is an indicator, Mrs. Cardeza favored bobbin laces like Valenciennes, Mechlin, and Point de Paris. She does not say whether her laces are antique pieces or even handmade. There seem to be few items of clothing or accessory that are made of, or, trimmed with lace, and there are evening coats, fur coats, handkerchiefs, petticoats, gowns, wrappers, dressing sacques, pillow slips, and bureau scarves all in varying types of lace. There are few garments that make me weak in the knees but a 1912 tea gown can take my breath away.

Image 7 . Embroidered lace tea gown, c. 1912 White cotton net, elbow L sleeves, narrow silhouette, heavily embroidered, needle lace bodice insertions, hem & side gores of handmade tape lace, F & B floating panels, crochet ball button trim, net lining, B 34″, W 26″, L 60″. Ohio State University

She does say that of her seven umbrellas and parasols, which she called “gamps” (see sidebar) four were made of Milanese, Brussels and appliqué lace and were purchased from Redfern. The combined purchase price of these four gamps was $650 ($15,892 today).

Image 8. Lace gamp

Gamp, Brussels lace, circa 1910. The term is derived from the name of a character in a Dickens novel. Sarah Gamp was an umbrella-wielding, gin soaked mid-wife who was nonetheless charming. She so endeared herself to readers of Martin Chuzzlewit, in which she had a prominent role, that fans began to refer to their umbrellas as gamps. The term is still used today.

Image 9. Mother of pearl and lace fan. Cardeza was in Hungary in 1912. Perhaps she purchased the fan she mentions in her inventory there. This is a Hungarian fan of the period.

Image 9a. Handkerchief Cardeza has several dozen lace handkerchiefs in the drawers of her trunks. Pictured is an example of point de Paris lace that she mentioned in her list

Of the more than 35 waists (blouses) in her trunks, many were made of the en mode chiffon or linen and were adorned with embroidery and/or Irish, filet and Venetian lace. The term waist could mean not just a blouse to pair with a skirt, but an over blouse to be worn over a delicate gown. Mrs. Cardeza paid as much as $450 for one waist designed by Redfern. By contrast, the Sears catalog for 1912 shows a black, embroidered silk chiffon waist for $4.50 (about $110.00 today).

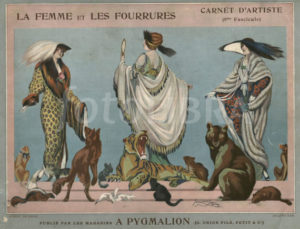

Image 10. Furs catalog from Brussels-based Pygmalion. 1912.

Inventory of Furs

Chinchilla coat ($6,000) New York

White baby lamb coat ($1,400) Russia

Chinchilla stole ($1,400 Austria

Ermine coat ($1400) New York

Mink stole and muff ($800) Russia

Near seal coat (800) Germany

Moleskin ($400) Paris

Silver fox stole (New York)

Ermine stole & muff ($180) Germany

Squirrel ($200)

Since the early 1600s, fur has been economically and socially important. Today, demand for fur has diminished considerably but until recent history, fur was a status symbol. Mrs. Cardeza packed or purchased along the way, at least twelve fur garments including coats, stoles and muffs. It would be interesting to know which furriers designed these pieces, but she only mentions where they were purchased. Perhaps her furs came from the likes of Drecoll, who designed fashions for the imperial family of Austria. The Brussels-based Pygmalion also provides an idea of the styles of the day. (To modern sensibilities, it is a bit macabre that the catalog seems to ask the the animals to advertise their own coats.) The insurance claim asserted that Mrs. Cardeza spent, $262,226 (in 2018 dollars) to stay fashionably toasty.

Image 11. Fur designed by Austrian couturier, Drecoll who was designer to the imperial family of Austria.

Accessories make the outfit of course, and although Mrs. Cardeza did not seem to have any shoes that cost more than $10, it did appear she had a glove fetish. For this trip, she had more than 75 pairs of kid leather, silk and suede gloves. There were almost an equal number of long and short ones. Apparently, unless they were asleep, in the bath, drinking or eating, ladies’ hands were gloved. It has been said that a lady never put on or removed her gloves in public. The rule makes clear why dinner was always after the opera. The most elegant opera gloves—over the elbow—could take a stretcher, a lot of glove powder, a ladies’ maid and as long as twenty minutes to inch all the way up. It would have been inelegant to try it in public. I can imagine ladies swanning into the ladies lounge of the Savoy Hotel (where there was a fainting couch) to have the uniformed ladies’ maid help them off with their gloves. When dinner was over there would be a trip back to the ladies lounge and more glove wrangling before farewells and the return trip home.

Image 12 . Glove powder container, a holdover from the Victorian era. Treenware.

Image 13. Kidskin opera gloves

Image 14. Glove stretcher. Birmingham sterling 1912

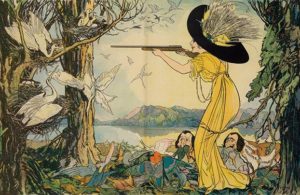

Today, we certainly see elegant hats at Ascot, the Kentucky Derby and English weddings. And always on Queen Elizabeth. She seems to be keeping up the notion that no respectable woman is seen outside her home without a hat. In 1912, hats were huge both in dimension and in importance as an accessory. Generally made of velvet, felt or straw, hats were adorned not only with tails and crest feathers of exotic birds but sometimes with their entire stuffed bodies.

Image 15. Egret feathers adorn hat in 1912. Note the shimmering fabric of her dress that seems to have a life of its own.

Image 16. Egret showing its most desirable hat trimming…its mating plummage.

Image 17. “Mary Stuart” aigrette in gold, silver, diamonds and pearls designed by Joseph Chaumet, circa 1910. Collection Chaumet Paris

By 1905; wearing feathers as personal adornment came under widespread criticism. Concerted efforts by newspapers like The New York Times, satirical magazine Puck, and the newly formed Audubon Society waged a public relations campaign that ultimately saved egrets, birds of paradise and other species from certain extinction. It was in the nick of time. According to the Times, “1911 saw just four feather trading firms sell approximately 223,490 bird corpses in London alone.” They charged the fashion industry with engaging in “murderous millinery.” I thought about Rose’s hat. Perhaps Titanic costume designer, Deborah Scott, left the feathers off to make her supportive of the cause. Perhaps I am just making that up but it pleases me to think that she did.

Image 18. Satirical magazine Puck (published from 1871 until 1918) mocks milliners as retrievers for women are really behind the practice called “murderous millinery”.

Charlotte Cardeza did not seem to be enlightened on this issue. She packed three aigrette feathers, one black, one white and one light blue. Together they cost $380.00 or more than the cost of a pound of gold. (At that time, gold traded at around $20.00 per ounce) She listed two pink “Elephant’s Breath Paradise” feathers for $125.00 and another without color description for $80.00. An additional pink paradise feather was $75.00. It is not clear if that is the price for an entire bird or just the tail feathers.

The entire Cardeza inventory deserves study and would take more digital ink to adequately illuminate than there are ones and zeroes to spend here. I did not mention the contents of the three crates. I also did not cover the jewelry she deposited with the Titanic purser that would be worth $2,561,000 today. Of course if it was actually found 12,500 feet below the surface of the Atlantic, it would be worth considerably more as a artifact of the catastrophic event.

Mrs. Cardeza did not receive the full value of her insurance claim. It probably made little financial difference to her. She could easily replace the items she lost. She died in 1939 leaving an estate of at least $52 million or the equivalent of almost $1,000,000,000 in today’s dollars.

Image 19. Charlotte Cardeza and Annie Moore Ward (undated).

Finally, Charlotte Cardeza did not pack a bathing suit for a journey on a ship with a heated pool. Or did she? Maybe the mysteriously named “one-piece albatross” was actually a swimming costume.

NOTES

1.Wilson, Andrew, Shadow of the Titanic: The Extraordinary Stories of Those Who Survived, narrated by Bill Wallis, Audible 2018 Audiobook

2.Daugherty, Greg, “Here’s What the Most Expensive Ticket on the Titanic Would Have Bought You” Money Magazine, online, April 14, 2016, accessed March 3, 2018

Dale Paige Talley is an author, historian and partner in Engaging History Productions, Inc. The non-profit coalition of historians, authors, actors, costume and set designers create custom events that bring history to life. Clients are typically museums, foundations and historical societies in and around Richmond, Virginia.

Contact: engagingfour@gmail.com

One reply on “Feathers, Furs and Lace: The Price of Fashion in 1912 by Dale P. Talley”

Thanks for finally writing about >Feathers, Furs and Lace: The Price of Fashion in 1912

by Dale P. Talley – Every Girl’s Dream <Loved it!